Inside Ray: What Happens When You Hit Start

Ray isn't just an API—it's a distributed company with executives, managers, and workers. Learn the runtime components (GCS, raylet, object store) and practical debugging steps for Kubernetes-based Ray clusters.

Everything looked perfect.

Our Ray cluster was running. The dashboard loaded. Every node showed green.

And yet—our training jobs just sat there. Pending. Forever.

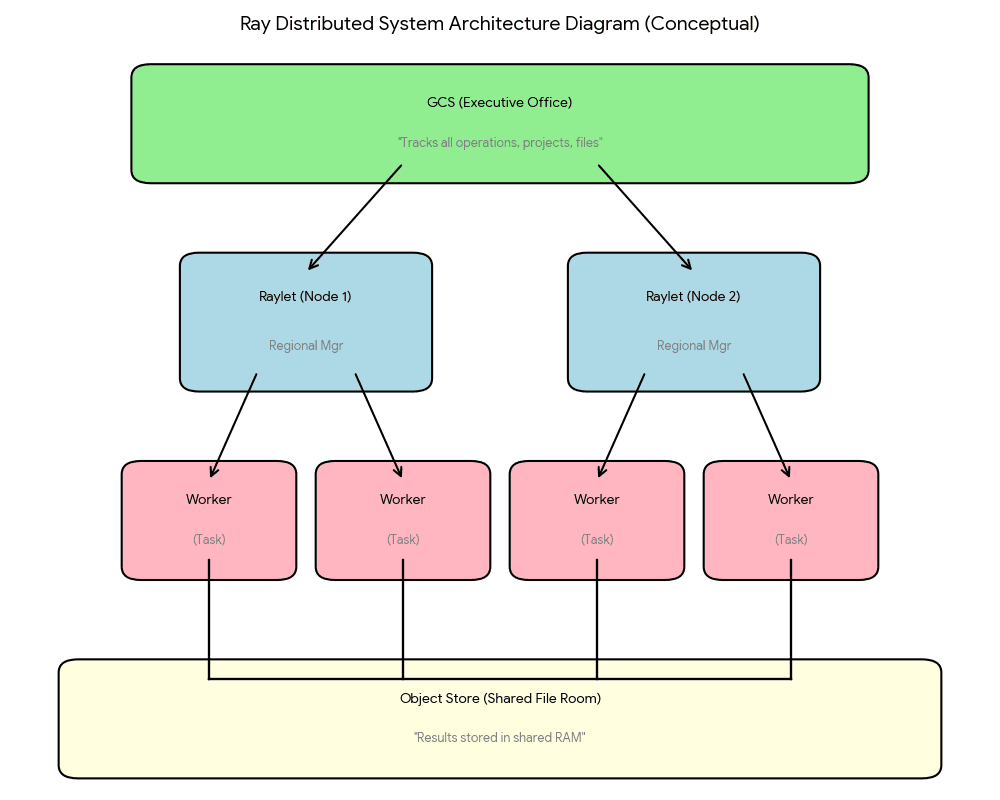

Here's what I learned that day: Ray isn't just an API that "makes Python distributed." We'll use a companies analogy to understand how ray works internally. So buckle up! Ray is like a company—with executives tracking operations, managers coordinating work, employees executing tasks, and a shared file room where everyone stores completed work.

Understanding that structure—who does what, how they communicate—turned debugging from guesswork into detective work.

At Mechademy, we'd spent weeks getting Ray onto AWS with Kubernetes. The infrastructure was finally up and running, but nothing would execute. We SSH'd into pods and saw Python processes running. Logs streamed from every component. But which ones actually mattered?

It felt like standing outside a glass building watching machines hum inside, unable to figure out what was broken.

You're not alone in that moment.

I spent hours in Ray's GitHub issues and community forums, and the pattern was always the same: clusters that start successfully but silently fail at execution. Kubernetes deployments where network policies block pod-to-pod communication. Cloud deployments where initialization scripts fail with cryptic errors that only surface at runtime. Clusters where services haven't finished starting, causing the whole system to hang.

Green status lights hiding invisible misconfigurations—blocked ports between nodes, missing environment variables, or storage that never mounted. The cluster looks healthy, but jobs never run.

That's when ray.init() stopped being an API call and became a survival skill. Once you understand which processes should exist, how they coordinate, and where they log, debugging stops feeling like magic and becomes systematic.

So I started reading Ray's startup path in the source code. What emerged was surprisingly elegant: a small set of cooperating processes that, once mapped, explain almost every "cluster is up but tasks won't run" scenario.

The breakthrough came when I stopped treating ray.init() as magic and began asking concrete questions:

- Is the GCS process running and can workers reach it?

- Are raylet processes registering and spawning workers?

- Is the object store mounted and accessible on each node?

For Kubernetes deployments, you can start debugging with:

# Check head pod logs for GCS startup and port kubectl logs -n <namespace> <ray-head-pod> -c ray-head | grep -i gcs # See worker/raylet logs kubectl logs -n <namespace> <worker-pod> -c ray-node | tail -n 200

Example success messages (vary by Ray version):

INFO gcs_server.py: GCS started on port 6379 INFO raylet.py: Raylet registered with GCS, node_id=...

Don't worry if those terms sound new—we'll unpack them. The key is that each question has a precise place to check: a log file, a dashboard entry, a process name. Once you know that map, the fog lifts.

The day we built that mental model, debugging went from hours to minutes. When a task stalled, we knew exactly where to look: Raylet logs for scheduling, GCS logs for cluster state, object-store metrics for memory pressure.

If Part 1 showed Ray as a black box that "just works," this part opens the box. Here's the company structure:

The GCS is the executive office tracking all operations. Each Raylet is a regional manager coordinating local teams. Workers are employees executing tasks. The object store is the shared file room where everyone accesses completed work.

Once you understand how the company is organized, the chaos makes sense.

Let's open the doors and step inside.

TL;DR: ray.init() starts a distributed system with GCS (metadata service), raylets (node managers), object stores (per-node shared memory), and workers. If tasks hang, check: GCS connectivity → raylet registration → worker health → object store status.

Two Ways to Start Your Company

When you call ray.init(), Ray makes a fundamental decision: should it start a new company, or connect to an existing one?

This isn't just API trivia. Understanding these two modes explains why your laptop behaves differently from your production cluster, and why debugging strategies change between development and deployment.

Local Mode: The Startup Office

On your laptop, ray.init() with no arguments launches everything:

import ray ray.init() # Starts executives, managers, workers, file room—everything

Within seconds, Ray spins up a complete distributed system on a single machine. You get the GCS (executive office), one Raylet (regional manager), several workers (employees), and an object store (shared file room). It's a fully functional company, just smaller.

This is perfect for development. You can test distributed code without deploying infrastructure. When something breaks, all the logs are on your machine. No remote access needed, no network debugging.

So when starting off, I would implore every engineer to run Ray locally first. Prototype training pipelines on laptop-sized data, verify the logic works, then deploy to cloud/clusters/wherever. Local mode helps catch 90% of bugs before they touch production.

Cluster Mode: The Enterprise

Production is different. You don't want computation on your laptop—you want a cluster of powerful machines working together.

At Mechademy, we deploy Ray clusters to AWS using Kubernetes. Our orchestration platform manages the infrastructure—launching head and worker pods, configuring networking, mounting storage. Once the cluster is running, we connect to it:

# We submit jobs to the cluster ray.init(address="ray://<cluster-service>:10001")

The cluster has one head node running coordination services (GCS, dashboard, scheduling) and multiple worker nodes providing computational muscle. Our platform becomes a client—we submit work, retrieve results, but don't execute anything locally.

The Decision Path

Inside Ray's initialization code, the logic is straightforward:

# Simplified view of what happens internally (not user code) def init(address=None, ...): if address is None: # No address? Start local company start_all_ray_processes() else: # Address provided? Connect to existing enterprise connect_to_cluster(address)

One parameter changes everything. address=None means "I'm the company." address="ray://..." means "I'm a client bringing work."

When to Use Each

| Scenario | Mode | Why |

|---|---|---|

| Writing new code | Local | Fast iteration, easy debugging |

| Running tests | Local | Reproducible, no infrastructure needed |

| Production training | Cluster | Scale to real data and compute |

| Managed workflows | Cluster | Central job orchestration |

Why This Matters for Debugging

When your local code works but the cluster fails, the problem is usually environmental:

- Local mode: Single process space, shared memory, no network

- Cluster mode: Multiple machines, network latency, distributed state

Those GCS connection errors we hit? They only appeared in cluster mode because worker pods couldn't reach the head node's GCS port through our network configuration. Locally, everything was localhost—no network to misconfigure.

Understanding the two modes helped us reproduce issues. We could test job submission logic locally before deploying to the cluster, catching workflow assumptions before they touched production infrastructure.

Next, let's see what actually starts when you call ray.init() in local mode. What processes launch? How do they coordinate?

Opening Day: The Startup Sequence

A note on specifics: Process names, port numbers, and configurations shown here are typical for recent Ray versions on Linux. Cloud deployments may vary—verify against your deployment logs. The concepts remain the same even when the specifics differ.

Let's watch what happens when you call ray.init() on your laptop:

import ray ray.init()

You'll see output like:

2024-11-16 10:30:15,234 INFO worker.py:1724 -- Started a local Ray instance. Dashboard running on http://127.0.0.1:8265

Behind that simple message, Ray just launched an entire distributed company. Let's see what's actually running.

What's Running on Your Machine

Open another terminal and run an example inspection:

ps aux | grep rayYou should see Ray-related processes for the GCS (metadata service), the raylet (node manager), worker processes, and the dashboard. Exact names and counts vary by Ray version and platform.

The Startup Steps

Step 1: Resource Assessment

Ray first surveys your machine—CPUs, GPUs, available shared memory. This is like assessing office capacity before hiring. Ray won't promise resources it can't deliver.

Step 2: Opening the Executive Office (GCS)

The GCS (Global Control Store) starts first. It's the operational hub tracking:

- Which offices (nodes) exist in the company

- What projects (tasks) are running or pending

- Where files (objects) are stored across the company

- Who has resources (CPUs, GPUs, memory) available

Every other component reports to the GCS: "I exist, here's my location, here's my capacity."

Step 3: Hiring Regional Management (Raylet)

The Raylet launches next—your regional manager coordinating local operations:

- Assigns work to available employees (workers)

- Manages resource allocation

- Coordinates file transfers between offices

The Raylet immediately checks in with the executive office:

"Executive team, this is Regional Office A. I have 8 employees available and 2GB of file room space."

Step 4: Setting Up the File Room (Object Store)

The object store allocates local shared memory (commonly from /dev/shm on Linux)—a per-node file room where task results live temporarily. When a node needs data that lives on another node, Ray's ObjectManager transfers it between the two local stores.

Multiple workers on the same node can access the same files without making copies—they just read from the shared cabinet. This zero-copy sharing is why Ray is fast for large data.

FYI, this is one my favorite things of ray and we will deep dive into it a lot more in a later post.

Step 5: Onboarding Workers

The Raylet spawns several worker processes upfront—your employees ready to execute work. Workers start idle, waiting for assignments from the regional manager.

Step 6: Installing the Metrics Dashboard

Finally, the dashboard starts (typically on port 8265, configurable via deployment settings):

Dashboard running on http://127.0.0.1:8265

Open that URL and you'll see real-time visibility into company operations: which employees are busy, project timelines, storage usage, logs from all departments.

The Check-In Process

Once everything's running, components coordinate:

- Raylet → GCS: "Regional Office online with 8 employees"

- GCS → Raylet: "Acknowledged. You're office_id abc123"

- Workers → Raylet: "We're ready for assignments"

- Dashboard → GCS: "Show me company status"

Every component registers metadata with the GCS—"I exist, here's my location, here's my capacity." GCS is the cluster ledger—it records and announces state, but raylets make most local scheduling decisions.

What You Can Observe

Try this:

import ray ray.init() # Check company resources print(ray.cluster_resources()) # Shows: CPUs, memory, object_store_memory # Open dashboard at http://localhost:8265

In the dashboard, click "Cluster" to see your office, "Jobs" to see current work, "Metrics" for resource graphs.

When Things Go Wrong

Remember those GCS connection errors? Understanding this startup sequence made debugging systematic:

- Symptom: Workers showed as idle, tasks pending

- Check: All processes running? ✅

- Check: Dashboard showed cluster? ❌

- Diagnosis: Workers couldn't reach GCS (network configuration)

- Fix: Update network policies to allow pod-to-pod traffic

Knowing what should start, and what should connect to what, is essential for diagnosis.

The Company Is Open

In under a second, ray.init() went from nothing to a fully coordinated distributed company. The executive office is tracking operations. Regional management is ready. Workers are standing by. The file room is prepared.

Now let's see what happens when you actually give them work to do.

Corporate Structure: How the Company Works

Now that you've seen the startup sequence, let's understand how these components actually work together. Each has a clear responsibility, and knowing who does what makes debugging systematic.

For deeper technical details, see the Ray Architecture documentation.

The Executive Office (GCS)

The GCS (Global Control Store) is the operational hub—not micromanaging, but tracking company-wide state so everyone can coordinate.

What it tracks:

- Offices: Which machines are part of the company (nodes)

- Projects: What work is running or pending (tasks)

- Files: Where work outputs are stored (objects)

- Resources: Who has CPUs, GPUs, memory available

When a regional manager needs to know "where is file abc123?" they check with the executive office.

So GCS is not micromanaging, but it is still a cluster coordinator. Not a dictator—more like a central HR & record system used by managers.

The Regional Manager (Raylet)

Each node has a Raylet that handles local operations—the on-site manager who knows what's happening in their office.

Two main responsibilities:

- Work scheduling: "I have 8 employees available, I can take this project" or "This project needs 4 GPUs, I don't have those—check with corporate"

- File transfers: "Project needs file abc123 from Office 2—fetch it" or "This result is 5GB, store it locally and tell corporate where it is"

The Raylet doesn't make company-wide decisions—it manages local resources and coordinates with the GCS when needed. This separation is why Ray scales.

The File Room (Object Store)

The object store is a shared-memory region on each node — a fast, local “filing cabinet” where task results are stored.

Why shared memory? Performance. When two tasks run on the same node:

- Task A writes its output into the local object store (shared memory)

- Task B reads the output directly from that shared memory

- Zero-copy, zero-serialization inside the node

This is why Ray can pass large arrays, DataFrames, or model outputs between workers efficiently.

Important: Each node has its own object store. There is no cluster-wide shared memory.

When a task on Node A needs data stored on Node B:

- The ObjectManager asks GCS where the object lives

- Performs a network transfer from Node B’s object store

- Materializes it in Node A’s object store

So within a node: zero-copy Across nodes: serialized network transfer

The Workers

Workers are Python processes that execute your actual code. When you call a Ray remote function, a worker runs it.

Workers are single-threaded and handle one task at a time. They're managed by their local Raylet, which decides who gets which assignment.

How They Communicate

Here's the flow when you submit work:

Your code → Raylet (regional manager)

↓

Raylet checks: Can my office handle this?

↓

If yes: Schedule to available worker

If no: Ask GCS for office with capacity

↓

GCS responds with available office

↓

Raylet transfers project to remote Raylet

↓

Remote Raylet schedules to their worker

↓

Worker executes, stores result in local file room

↓

Raylet updates GCS with completion status

↓

Your code retrieves result

No component commands another. They coordinate through the GCS and route work through the Raylet network.

Why This Structure Scales

Centralized systems break at scale. If every decision required executive approval, the C-suite becomes a bottleneck.

Ray avoids this:

- Raylets make local decisions (no round-trip to GCS for every task)

- GCS only tracks metadata (not data itself)

- File rooms are per-office (no central data repository)

- Workers are autonomous (parallel execution without constant coordination)

This is why Ray handles thousands of nodes and millions of tasks.

At Mechademy, understanding this structure changed how we debug. We stopped asking "why isn't Ray working?" and started asking specific questions: "Is the GCS accessible? Is the Raylet assigning work? Are workers accessing the file room?"

Each component logs separately, fails independently, and can be diagnosed in isolation.

Your First Project: Through the Company

Let's watch a project flow through the system:

import ray ray.init() @ray.remote def process_data(x): return x * 2 result_ref = process_data.remote(5) result = ray.get(result_ref) print(result) # 10

Simple code. Complex coordination. Let's trace what happens.

Step 1: Function Registration

The @ray.remote decorator doesn't execute anything—it registers the function with the company. Behind the scenes, Ray wraps your function, serializes it, and registers it with the GCS so any office in the company can execute it.

Think of this as creating a standard operating procedure. Once filed with corporate, any regional office can run it.

Step 2: Project Submission

Calling .remote(5) submits a work order to your regional manager specifying what work to do and what resources it needs.

Step 3: Work Scheduling

The regional manager decides where this runs:

"Can I handle this locally? Yes—I have available workers. Schedule to Worker 3."

If the local team is overloaded, the Raylet coordinates with the GCS to find an office with capacity.

Step 4: Execution

The assigned worker retrieves the function code from the GCS registry, executes it, and stores the result in the local file room:

"Executed x * 2 with x=5, got result=10. Filed in object store as object_xyz."

Step 5: Result Retrieval

When you call ray.get(), you're asking: "Where's my completed work?"

The regional manager checks the local file room first. If the result is in another office, it fetches it through the corporate network.

The Complete Flow

1. Register procedure: @ray.remote 2. Submit project: process_data.remote(5) 3. Assign work: Raylet finds available worker 4. Execute: Worker runs x * 2, stores result 5. File output: Goes to object store 6. Retrieve: ray.get() fetches from file room

Knowing the flow—submit → assign → execute → file → retrieve—made it clear where to investigate. Each step has logs, each component has clear responsibility.

What's Next

You Now Understand the Runtime

When you call ray.init(), you're launching a distributed company with:

- Executive coordination (GCS)

- Regional management (Raylet)

- Shared file storage (Object Store)

- Execution workers

- Operational visibility (Dashboard)

Coming Up in Part 3: Tasks, Actors, and Execution

Now that you know how the company works, we'll explore what it can handle:

- Individual projects (tasks) vs ongoing departments (actors)

- When to use each

- Advanced patterns

Try It Yourself

import ray ray.init() # Open http://localhost:8265 @ray.remote def debug_task(): import time, socket time.sleep(3) return f"Executed on {socket.gethostname()}" refs = [debug_task.remote() for _ in range(5)] results = ray.get(refs) print(results)

Watch how the regional manager distributes work, workers execute in parallel, and the dashboard shows real-time progress.

Understanding the runtime isn't academic—it's practical. When something breaks in production, you'll know exactly where to look: executive office connectivity, regional manager logs, worker capacity, file room pressure.

See you in Part 3.