Scheduling and Resource Management

Understanding Ray's intelligent scheduler—from hybrid scheduling and resource control to coordination tuning and data locality optimization.

Your code was perfect. The logic was sound. Ray was distributing work across the cluster.

And yet—everything was slow.

Not "my algorithm needs optimization" slow. Not "I need more GPUs" slow. The kind of slow where you watch the dashboard and see workers sitting idle while tasks pile up in the queue. Available CPUs everywhere. No memory pressure. Just... waiting.

I've seen this pattern in Ray's GitHub issues and community forums more times than I can count. Teams with powerful clusters—hundreds of cores, dozens of GPUs—watching their distributed system crawl. The usual suspect? They assume the problem is computational. "We need bigger machines." "Let's add more nodes."

But sometimes the bottleneck isn't compute. It's coordination.

At Mechademy, we hit this when scaling our feature engineering pipeline. We were generating millions of small tasks—one per machine configuration, per time window, per feature set. Each task was cheap (milliseconds of work), but there were so many of them that Ray's coordination layer started drowning.

The symptoms were subtle at first. Dashboard response times crept up. Task scheduling latency increased from milliseconds to seconds. Workers were available, but tasks weren't landing fast enough. We weren't compute-bound—we were coordination-bound.

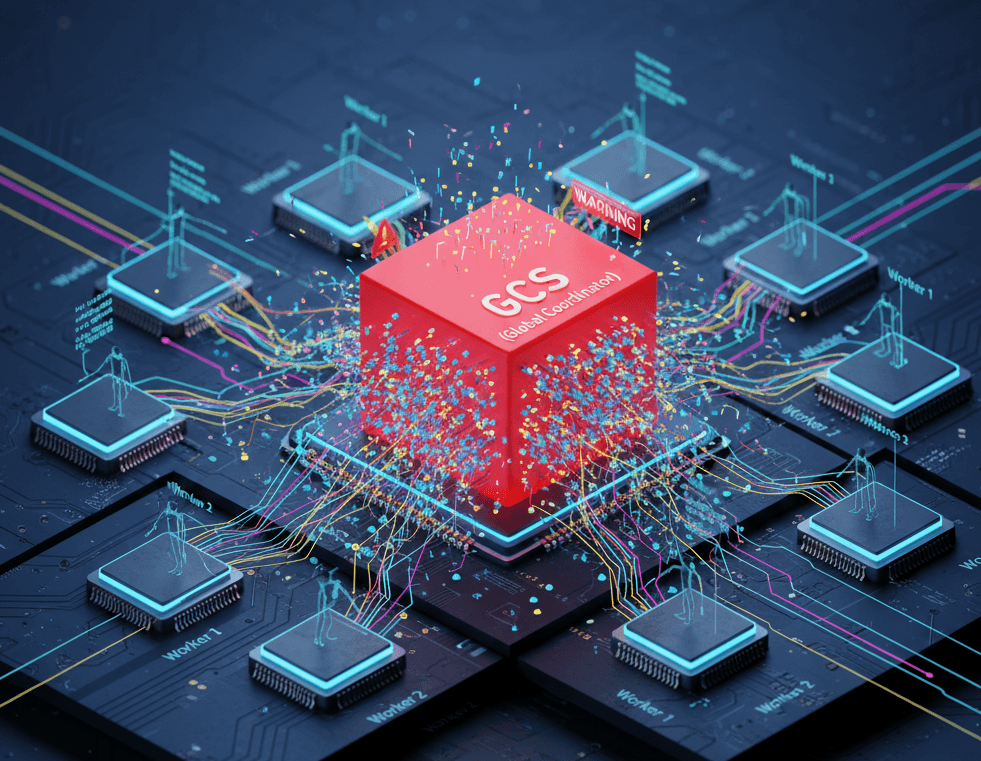

The GCS (the executive office tracking everything) was getting hammered with status updates from every Raylet: "Task 1 started." "Task 1 finished." "Task 2 started." Multiply that by millions of tasks, and the central coordinator becomes a traffic jam.

Here's what surprised me: the fix wasn't adding more resources. It was reducing chatter.

Ray has a tuning parameter called metrics_report_interval_ms that controls how often Raylets send metrics to the GCS. By default, it's 10 seconds—fine for most workloads, but when you're generating tasks faster than the GCS can process updates, you need breathing room. We bumped it to 30 seconds:

ray.init(_system_config={"metrics_report_interval_ms": 30000})Suddenly, the GCS stopped being a bottleneck. Tasks flowed. Workers stayed busy. Same cluster, same code, different coordination strategy.

That moment taught me something fundamental about distributed scheduling: it's not just about finding available resources. It's about balancing where work runs with how much coordination that decision requires.

This is what Part 4 is about. Not just "Ray finds an available worker and runs your task there"—but the intelligence behind those decisions. How does Ray know which node has the right resources? When does it optimize for data locality versus load balancing? How do you control placement when you need specific hardware? And critically—how do you tune the system when coordination itself becomes the bottleneck?

If Part 2 showed you the components and Part 3 showed you the execution models, Part 4 is about the brain that ties it together: the scheduler that decides where everything runs, and how to make it work at scale.

Let's start with the basics: when you call task.remote(), how does Ray decide where it runs?

The Basics: How Ray Decides Where

When you call task.remote(), Ray doesn't just pick a random worker and ship your code there. There's a multi-step dance between the components you met in Part 2—your local Raylet, the GCS, and remote Raylets.

Let's watch what happens with a simple example:

import ray

ray.init()

@ray.remote

def process_data(x):

return x * 2

result = ray.get(process_data.remote(10))Step 1: Local First

Your code submits the task to your local Raylet—the regional manager on your machine. The Raylet asks: "Can I handle this here?"

To decide, it checks:

- Resource requirements: Does this task need CPUs, GPUs, memory?

- Available workers: Do I have an idle worker that meets those requirements?

- Data locality: Are the task's arguments already in my local object store?

If everything checks out, the Raylet assigns the task to a local worker immediately. No network hop. No coordination overhead. Just local scheduling.

This is why Ray is fast for single-machine workloads—most tasks never leave your node.

Step 2: Spillback When Necessary

But what if your local Raylet can't handle it? Maybe all workers are busy, or the task needs 4 GPUs and you only have 2.

This is where spillback happens. The Raylet doesn't make a cluster-wide decision itself—instead, it asks the GCS: "Who has capacity?"

The GCS maintains the global view:

- Which nodes are alive

- What resources each node has

- Which nodes are overloaded

The GCS responds with a suggestion: "Try node 192.168.1.10—it has available GPUs."

Your local Raylet then forwards the task request to that remote Raylet. The remote Raylet checks its local state, and if it has capacity, assigns the task to one of its workers.

Step 3: The Worker Lease

Technically, what the Raylet is doing is requesting a worker lease. It's not asking "run this task"—it's asking "give me a worker who can run this task."

Once the lease is granted, the task gets shipped to that worker along with its arguments (or references to arguments in the object store). The worker executes, stores the result, and becomes available again.

Default Behavior: Hybrid Scheduling

This two-level approach—local decisions when possible, global coordination when necessary—is what makes Ray scale. Raylets handle the fast path (local scheduling) without consulting the GCS. The GCS only gets involved when a Raylet can't satisfy a request locally.

This is called hybrid scheduling: local by default, global when needed.

What You Don't Specify

Notice what we didn't tell Ray:

- Which node to run on

- Which worker to use

- How to balance load across the cluster

Ray figured it out based on resource availability and locality. For most workloads, this default behavior is exactly what you want—tasks land on nodes with capacity, and Ray keeps the cluster busy.

But what if you need more control? What if you have GPUs on specific nodes, or you want tasks to run close to certain data? That's where explicit resource requirements come in.

Next, we'll see how to guide Ray's scheduling decisions.

Controlling Placement

Ray's default scheduling works well—until you need something specific. Maybe you have GPUs on certain nodes. Maybe you want to spread work evenly for fault tolerance. Or maybe you want to run massive workloads without paying for idle resources.

That's when you stop accepting Ray's defaults and start designing your placement strategy.

Resource Requirements: The Basics

The simplest control is telling Ray what a task needs:

@ray.remote(num_cpus=4, num_gpus=1)

def train_model(data):

# Needs 4 CPUs and 1 GPU

return model.fit(data)Now the Raylet won't schedule this task on a node that doesn't have a GPU. If all GPU nodes are busy, the task waits rather than running on the wrong hardware.

You can also specify requirements per call:

# Override the default for this specific task

train_model.options(num_cpus=8, num_gpus=2).remote(large_dataset)This is how you match compute to workload: lightweight tasks get modest resources, heavy training gets the powerful hardware.

Custom Resources: Beyond CPUs and GPUs

What if you have specialized hardware—specific instance types, nodes with NVMe drives, or machines in certain availability zones?

Ray lets you define custom resources. When you start a node, you tag it:

ray start --head --resources='{"nvme": 1, "region:us-west": 1}'Then you request it:

@ray.remote(resources={"nvme": 1})

def process_with_fast_storage(data):

# Guaranteed to run on a node with NVMe

return crunch(data)Custom resources are labels. Ray doesn't check if the hardware exists—it just routes tasks to nodes that claim to have it. You're responsible for the tagging; Ray handles the routing.

The Head Node Pattern: Maximum Power, Minimum Cost

Here's a pattern I designed at Mechademy that changed how we think about Ray clusters: make the head node tiny and prevent it from running tasks.

The problem: we need massive compute for training (dozens of GPUs, hundreds of CPUs), but only sporadically. We can't afford to keep that running 24/7, but spinning up infrastructure for every job wastes time.

The solution: a persistent, tiny head node that only coordinates, combined with autoscaling workers that appear on-demand.

# On the head node - no task execution

ray start --head --num-cpus=0 --num-gpus=0By setting num_cpus=0, you're telling Ray: "This node is for coordination only. Schedule zero tasks here."

The head runs the GCS, the dashboard, and cluster metadata—all lightweight services. It stays up continuously (we use a small AWS instance, costs maybe $50/month). Workers autoscale from zero to hundreds based on workload.

When a training job arrives:

- Head node receives the job (it's always listening)

- Autoscaler spins up GPU workers (takes 2-3 minutes)

- Tasks run on the workers

- Workers scale back to zero when idle

We get supercomputer-scale compute when needed, and pay almost nothing when idle. No DevOps fire drills, no manual cluster management. The head orchestrates everything.

This pattern is why Ray scales so well for bursty ML workloads. Your coordination layer is always available; your execution layer appears and disappears with demand.

Scheduling Strategies: Controlling Distribution

Sometimes you want to override Ray's locality bias. The SPREAD strategy distributes work across the cluster instead of packing it locally:

@ray.remote(scheduling_strategy="SPREAD")

def distributed_task():

return process()

# Tasks spread across all nodes

[distributed_task.remote() for _ in range(100)]This is useful for fault tolerance—if tasks are spread across nodes, a single node failure doesn't kill your entire job.

Placement Groups: Gang Scheduling

When you need a set of tasks to run together—like distributed training where all workers must communicate constantly—placement groups guarantee coordinated placement.

Without placement groups, Ray might scatter your 4 training workers across 4 different nodes. They'd work, but every gradient exchange would cross the network. Slow.

Placement groups let you say: "These tasks are a team. Keep them together."

from ray.util.placement_group import placement_group

from ray.util.scheduling_strategies import PlacementGroupSchedulingStrategy

# Reserve 4 GPUs on the same node

pg = placement_group([{"GPU": 1}] * 4, strategy="STRICT_PACK")

ray.get(pg.ready())

# All actors use the same placement group

@ray.remote(num_gpus=1)

class TrainingWorker:

pass

workers = [

TrainingWorker.options(

scheduling_strategy=PlacementGroupSchedulingStrategy(

placement_group=pg

)

).remote()

for _ in range(4)

]The STRICT_PACK strategy ensures all 4 actors land on the same node. If Ray can't satisfy that, the placement group creation fails rather than silently spreading workers across nodes where communication would be slow.

This is critical for distributed training where workers exchange gradients every batch. Co-locating them turns network overhead into shared-memory speed. The difference between minutes and hours for large models.

Placement Group Tuning

When using placement groups with autoscaling clusters, you might need to adjust timeouts:

containerEnv:

- name: RXGB_PLACEMENT_GROUP_TIMEOUT_S

value: "600" # Wait up to 10 minutes for resourcesPlacement groups are atomic—if Ray can't reserve all bundles immediately, it waits. With autoscaling, nodes might take minutes to spin up. The default timeout might be too aggressive when you're willing to wait for resources rather than fail fast.

At Mechademy, with our autoscaling worker setup, we set this to 10 minutes. Training jobs can afford to wait for GPU nodes to appear rather than failing immediately. The head node stays cheap and always-on while workers provision on-demand.

Next, let's return to that GCS bottleneck from the opening. What happens when your cluster generates tasks faster than the coordination layer can handle?

The Coordination Tax: Scheduling at Scale

Ray's scheduling is elegant—until you throw millions of tasks at it.

The hybrid model (local scheduling + global coordination) works beautifully for most workloads. But when you scale to truly massive task counts, something subtle starts to break: the coordination overhead compounds.

The Problem: Task Event Storms

Here's what most people don't realize: Ray doesn't just schedule tasks—it tracks them. Every task generates events:

- Task started

- Task status changes

- Task completed

- Profiling data for the dashboard

These events feed the dashboard, the State API, and your monitoring tools. They're what make Ray observable. But they're also data that needs to flow from workers → Raylets → GCS.

For a 10-node cluster running steady-state workloads, this is nothing. Events trickle in at a manageable rate. The GCS processes them, the dashboard updates, everyone's happy.

But when you generate millions of short-lived tasks?

At Mechademy, we were spawning millions of feature engineering tasks—each taking milliseconds to complete. Suddenly, every worker was generating thousands of task events per second. The GCS—designed for coordination, not high-frequency event ingestion—started falling behind.

Tasks were completing, but the dashboard showed them as pending. New tasks waited in the queue while the GCS processed the backlog of events from already-finished work. We weren't compute-bound—we were event-bound.

The Solution: Tuning Event Reporting

Ray exposes several knobs to control this overhead. The key parameters:

containerEnv:

# How often workers report task events to the GCS

- name: RAY_task_events_reporting_interval_ms

value: "1000" # Report every 1 second (default: 100ms)

# How often the GCS cleans up old task events

- name: RAY_task_events_cleaning_interval_ms

value: "30000" # Clean every 30 seconds (default: 10s)The first parameter (reporting_interval) controls how often workers batch and send task events. The default (100ms) means events flow almost in real-time. For massive task counts, increasing this to 1 second reduces event traffic by 90% while still keeping the dashboard reasonably current.

The second parameter (cleaning_interval) controls how often the GCS garbage-collects old events. Increasing this reduces GCS CPU overhead at the cost of higher memory usage temporarily.

The Tradeoff: Visibility vs Throughput

Here's the counterintuitive insight: sometimes the best optimization is to report less.

By increasing the reporting interval from 100ms to 1 second, we cut event traffic dramatically. The coordination overhead dropped. Tasks flowed.

The cost? The dashboard updates less frequently. Your metrics lag by up to 1 second instead of 100ms. For development, that's barely noticeable. For production jobs processing millions of tasks, it's a non-issue—you care about completion, not real-time progress bars.

Diagnosing Event Bottlenecks

How do you know when event overhead is your problem?

Watch the dashboard's own responsiveness. If the dashboard itself is slow to load or update, the GCS is overwhelmed processing events. Check these signals:

- Dashboard lag: Queries to cluster status take seconds

- Task scheduling latency: Workers idle while tasks queue

- GCS logs: Look for "event buffer full" warnings

- Mismatch: Workers show available, dashboard shows zero capacity

If you see these symptoms with available compute, you're event-bound, not compute-bound.

When Does This Matter?

Most teams never hit this. If you're running hundreds of tasks, or even tens of thousands, the defaults work fine. You care about this when tasks complete in milliseconds and you're generating millions per job across 20+ nodes—that's when coordination becomes the ceiling.

The beauty of Ray is that these knobs exist. The scheduling model is tunable. You can optimize for real-time visibility or maximum throughput—just know which problem you're solving.

Next, let's look at another scheduling optimization Ray does automatically: keeping data close to computation.

Data Locality: The Invisible Optimization

We've talked about how Ray decides where to run tasks—resource requirements, custom resources, explicit strategies. But there's one more factor Ray considers automatically: where the data already lives.

The Problem with Network Transfers

Imagine you have a 5GB dataset stored in the object store on Node A. Your task needs that data. If Ray schedules the task on Node B, it first has to transfer 5GB across the network. Even on a fast cluster network (10 Gbps), that's 4 seconds of transfer time before the task can even start.

Now imagine you're running 1,000 tasks that all need that same 5GB dataset. If they all land on Node B, you've wasted 4,000 seconds (over an hour) just moving data around.

Ray's Solution: Locality-Aware Scheduling

Ray tracks where objects live in the distributed object store. When scheduling a task, if the task arguments are large and already present on a specific node, Ray prefers to schedule the task there.

This is automatic. You don't request it. Ray just does it.

import ray

import numpy as np

# Create a large dataset on Node A

large_data = ray.put(np.random.rand(1000, 1000, 100)) # ~800MB

@ray.remote

def process(data):

return data.sum()

# Ray will try to schedule this on the node where large_data lives

result = process.remote(large_data)The data stays put. The computation moves to the data.

When Locality Matters

This optimization is most impactful when task arguments are large (tens of MB or more), shared across multiple tasks, and transfer time rivals execution time. For small arguments (a few KB), Ray just serializes them inline and sends them with the task—negligible overhead.

The Limits

Locality is a preference, not a guarantee. If the node with the data is overloaded or doesn't have the required resources, Ray schedules the task elsewhere and transfers the data.

You can also override locality with explicit scheduling strategies like SPREAD, which distributes tasks across the cluster regardless of data location.

The Practical Impact

At scale, locality-aware scheduling is invisible but powerful. Your XGBoost training data stays on specific nodes. Your preprocessing pipeline keeps intermediate results local. Tasks naturally cluster around their data.

This is why Ray's object store exists—not just for storage, but for smart, locality-driven scheduling. The data doesn't move unless it has to.

And when it does move, Ray handles it transparently. You write code that looks single-machine. Ray makes it distributed.

That's the scheduling story: default intelligence, explicit control when needed, and automatic optimizations working behind the scenes.

You Now Understand Ray's Scheduler

When you started this post, scheduling was a black box—"Ray puts tasks on workers somehow."

Now you know the intelligence behind those decisions:

- Hybrid scheduling: Local decisions when possible, global coordination when needed

- Resource control: Explicit requirements, custom resources, placement groups

- Coordination tuning: Event reporting intervals when you hit scale

- Locality optimization: Data stays put, computation moves to the data

You understand that scheduling isn't just "find available resources"—it's balancing placement, coordination overhead, and data movement. You know when to use the defaults and when to intervene.

Coming Up in Part 5: The Object Store

We've mentioned the object store repeatedly—data locality, zero-copy sharing, per-node memory. Part 5 dives deep:

- How Plasma actually works under the hood

- Memory management and spilling

- When objects move between nodes

- Sizing and tuning for your workload

Scheduling isn't magic—it's observable, tunable, intelligent.

See you in Part 5.