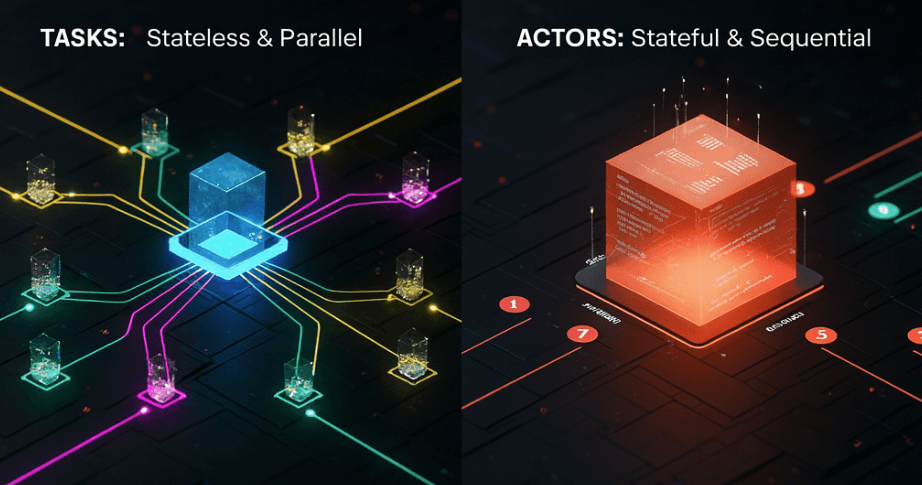

Tasks, Actors, and the Execution Model

Understanding Ray's two execution models—stateless tasks for parallel work and stateful actors for coordination—and when to use each.

Imagine you're running an office.

Some work is quick and one-off: "photocopy these documents," "send this email," "update this spreadsheet cell." You don't need the same person doing it, and they don't need to remember anything afterward. Any available employee can pick it up, finish it, move on.

Other work needs someone who stays with the project. Managing a client account means remembering conversation history, tracking what's been delivered, knowing what comes next. You can't switch account managers mid-project—the context would be lost. That person needs continuity.

Distributed computing has the same split.

When I started building ML systems at Mechademy, I thought scaling meant throwing @ray.remote on everything. Feature engineering? Remote function. Model training? Remote function. Progress tracking? Remote function. If it needed to run in parallel, make it remote.

The code ran. But something felt wrong.

Our model training would reload the entire XGBoost model from disk every time we checked progress. Our artifact generator would reinitialize plotting libraries for every single graph. We were treating everything like those quick office tasks—one-off jobs where the employee forgets everything after completion.

But ML pipelines aren't all one-off tasks. Some things need to remember.

A training coordinator managing hundreds of runs needs to know which hyperparameters it's testing, where it left off, what's already checkpointed. A model server handling inference requests needs to load the model once and keep it ready—not reload it for every prediction.

That's when I saw this in the Ray docs:

@ray.remote

class ModelServer:

def __init__(self):

self.model = load_model() # Load once

def predict(self, data):

return self.model(data) # Reuse foreverWait—classes, not just functions? State that persists between calls?

The office analogy clicked. Ray gives you both types of employees: tasks are the one-off jobs that any available worker can handle in parallel. Actors are the dedicated account managers who stick with a project and remember everything that's happened.

At Mechademy, this distinction transformed our architecture. Actors for the training coordinators that manage long-running jobs and track state. Tasks for the parallel feature engineering across thousands of machine configurations. Actors for artifact generators that accumulate plots throughout training. Tasks for the batch predictions that don't need memory.

The real breakthrough? Actors can delegate tasks. Your training coordinator (actor) holds the context and continuity, but when it needs 100 features computed, it dispatches 100 tasks to the employee pool. The dedicated manager orchestrates; the general staff executes.

Once you see this pattern, Ray stops feeling complicated and starts feeling elegant.

If Part 2 showed you the office structure that Ray builds when you call ray.init(), Part 3 is about understanding the two types of work assignments: the quick one-off jobs anyone can handle, and the ongoing projects that need a dedicated manager who remembers the full context.

Let's start with the basics: what actually is a task, and what actually is an actor?

Tasks: The One-Off Assignments

A task is Ray's simplest execution unit—a function that runs once, returns a result, and forgets everything.

import ray

ray.init()

@ray.remote

def process_feature(data):

# Do some computation

return data * 2

# Submit the task

result_ref = process_feature.remote(10)

result = ray.get(result_ref) # 20When you call process_feature.remote(10), here's what happens:

- Ray packages your function and arguments

- The Raylet finds an available worker

- That worker executes the function

- The result goes into the object store

- The worker becomes available for the next task

No memory between calls. No state. If you call process_feature.remote(20) next, it might run on a completely different worker. The function doesn't know—and doesn't care—what happened before.

This is perfect for parallel, independent work. Need to process 1,000 data batches? Spawn 1,000 tasks. Each runs independently, and Ray distributes them across your cluster.

Actors: The Dedicated Project Managers

An actor is different—it's a class instance that lives on a specific worker and maintains state between method calls.

@ray.remote

class ProgressTracker:

def __init__(self):

self.completed = 0

self.failed = 0

def mark_complete(self):

self.completed += 1

return self.completed

def mark_failed(self):

self.failed += 1

def get_stats(self):

return {"completed": self.completed, "failed": self.failed}

# Create the actor (stays alive)

tracker = ProgressTracker.remote()

# Call methods (same instance, remembers state)

tracker.mark_complete.remote()

tracker.mark_complete.remote()

tracker.mark_failed.remote()

stats = ray.get(tracker.get_stats.remote())

# {"completed": 2, "failed": 1}When you create an actor with ProgressTracker.remote():

- Ray spawns a dedicated worker process

- The

__init__method runs once - The actor stays alive, waiting for method calls

- All methods run on that same worker, one method call at a time

- State persists between calls

That last point is important: if you call three methods on an actor, they execute in order—the second waits for the first to finish, the third waits for the second. The actor processes its method queue sequentially.

This is your dedicated account manager. They remember everything: previous conversations, what's been delivered, what's pending. You can query them anytime, and they'll give you the current state. But they handle one request at a time—they can't take two phone calls simultaneously.

Side by Side: The Key Difference

# Task: Stateless, runs anywhere

@ray.remote

def count_words(text):

return len(text.split())

# Each call is independent

count1 = count_words.remote("hello world")

count2 = count_words.remote("foo bar baz")

# Different workers, no shared memory

# Actor: Stateful, runs on dedicated worker

@ray.remote

class WordCounter:

def __init__(self):

self.total = 0

def count_and_accumulate(self, text):

words = len(text.split())

self.total += words

return self.total

counter = WordCounter.remote()

total1 = counter.count_and_accumulate.remote("hello world") # Returns 2

total2 = counter.count_and_accumulate.remote("foo bar baz") # Returns 5

# Same worker, state accumulates across calls

Quick Comparison

| Feature | Task | Actor |

|---|---|---|

| State | Stateless | Stateful |

| Worker | Any available | Dedicated |

| Execution | Parallel (many tasks at once) | Sequential (one method at a time) |

| Use case | Independent operations | Coordination, memory |

| Syntax | @ray.remote on function | @ray.remote on class |

| Calling | func.remote() | actor.method.remote() |

Both use @ray.remote, but they behave completely differently. Tasks are the general employee pool—anyone can handle any job. Actors are specialized managers—they own their domain and remember their context.

At Mechademy, we use tasks for feature engineering (each batch is independent) and actors for training coordinators (they need to track progress across many steps). The pattern emerges naturally once you understand the distinction.

But knowing the difference is just the start. The real question is: when do you use which?

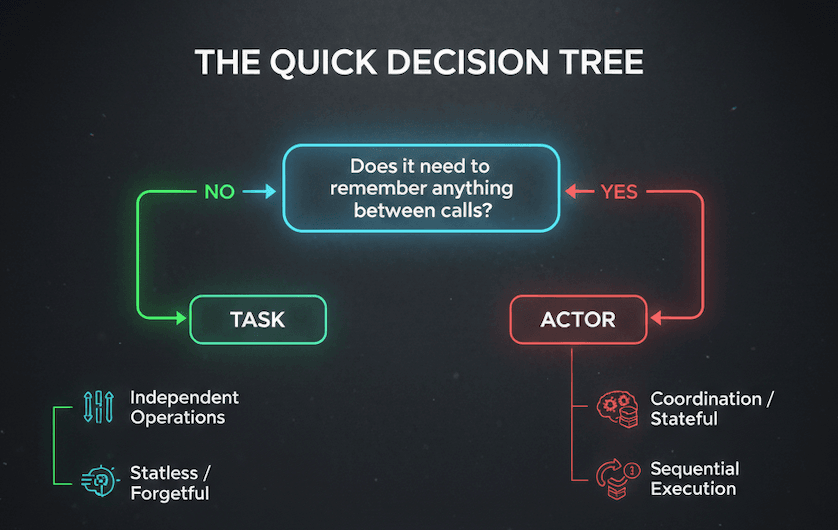

The Quick Decision Tree

Here's the simplest heuristic:

Does it need to remember anything between calls?

- No → Use a task

- Yes → Use an actor

Will the same logic run thousands of times in parallel?

- Yes → Use tasks

- Maybe, but with shared state → Use an actor (or multiple actors)

Does it involve expensive initialization (loading models, DB connections)?

- Yes → Use an actor (initialize once, reuse forever)

- No → Use a task

That covers 90% of cases. Let's see it in practice.

Tasks: Independent and Parallel

Perfect for work that doesn't need memory between calls:

# Processing 10,000 independent files

@ray.remote

def preprocess_file(filename):

return transform(read(filename))

results = ray.get([preprocess_file.remote(f) for f in files])Each file processes independently. No shared state. Any worker can handle any file. This is what tasks excel at.

Actors: Stateful and Expensive

Use actors when initialization is costly or state needs to persist:

# Serve predictions without reloading model

@ray.remote

class ModelServer:

def __init__(self):

self.model = load_model() # Once

def predict(self, data):

return self.model.predict(data) # Reuse forever

server = ModelServer.remote()The model loads once and stays in memory. Every prediction reuses it. This pattern—expensive init, cheap reuse—is where actors shine.

Common Mistakes

Reloading expensive resources in tasks: If you're loading the same model or opening the same connection on every call, use an actor instead. The initialization overhead will dominate your runtime.

One giant actor for parallel work: If your actor is processing 1,000 independent items sequentially, use tasks instead. Actors handle one method at a time—don't force them to do embarrassingly parallel work.

Overthinking it: Start with tasks. Add actors only when you need state or expensive initialization. Most distributed work is stateless, and tasks are simpler.

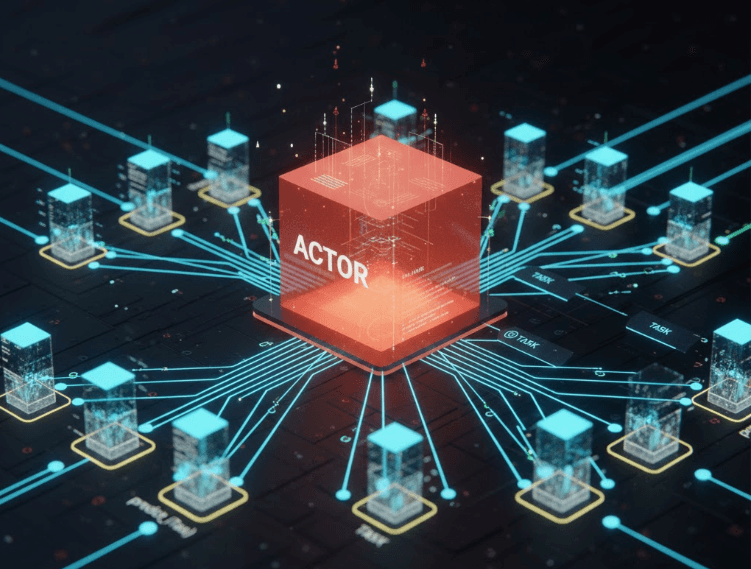

The Real Power

The pattern that emerges in production isn't tasks or actors—it's tasks and actors working together.

Actors hold expensive state. Tasks do parallel execution. An actor loads the model once, then dispatches prediction tasks across the cluster. A training coordinator tracks progress (actor) while spawning feature engineering tasks.

That's the pattern we'll explore next: how actors orchestrate tasks.

When State Meets Scale

Here's the pattern that makes Ray powerful: actors hold the context, tasks do the work.

Remember, actors process one method at a time—they're sequential. But inside that method, they can spawn hundreds of parallel tasks. The actor coordinates; the tasks execute.

Let's see it in action.

Example: Batch Prediction with Progress Tracking

You need to run predictions on 10,000 images. You want to track progress and report statistics, but the actual predictions should run in parallel.

import ray

@ray.remote

def predict_image(image_path, model_ref):

"""Stateless task - processes one image"""

image = load_image(image_path)

# Get the model from object store

model = ray.get(model_ref)

return model.predict(image)

@ray.remote

class PredictionCoordinator:

def __init__(self, model):

# Store model in object store once, keep reference

self.model_ref = ray.put(model)

self.completed = 0

self.failed = 0

def process_batch(self, image_paths):

"""Spawn parallel tasks, track results"""

# Dispatch tasks - pass ObjectRef, not the model itself

tasks = [

predict_image.remote(path, self.model_ref)

for path in image_paths

]

# Wait for completion and update stats

results = ray.get(tasks)

self.completed += len(results)

return {"completed": self.completed, "batch_size": len(results)}

def get_progress(self):

return {"completed": self.completed, "failed": self.failed}

# Create coordinator with trained model

coordinator = PredictionCoordinator.remote(trained_model)

# Process in batches

for batch in chunked(image_paths, 100):

stats = ray.get(coordinator.process_batch.remote(batch))

print(f"Progress: {stats}")

What's Happening Here

The PredictionCoordinator actor:

- Holds state: tracks completed and failed counts

- Dispatches work: spawns 100 parallel prediction tasks

- Aggregates results: updates statistics after each batch

- Responds to queries:

get_progress()returns current state

The predict_image tasks:

- Run in parallel: 100 images process simultaneously

- Scale automatically: Ray distributes across available workers

- Stay stateless: no memory between predictions

The actor is your progress tracker and coordinator. It processes batches sequentially, but within each batch, predictions run in parallel across your cluster.

This is the pattern everywhere in production: the stateful thing orchestrates, the stateless things execute. Model servers dispatching inference tasks. Training coordinators spawning feature engineering. Experiment managers launching trials.

State in one place. Execution distributed everywhere.

Now you understand what tasks and actors are, when to use them, and how they work together. But there's one more piece: what happens under the hood when you call .remote()?

The Magic of @ray.remote

When you decorate a function or class with @ray.remote, Ray wraps it so it can run anywhere in the cluster.

Here's what happens:

@ray.remote

def process_data(x):

return x * 2Ray serializes your function using cloudpickle. When a worker needs to run your task, it receives the serialized function code, deserializes it, and executes it. This happens automatically—you just call .remote().

Note: cloudpickle can serialize most Python objects, but some things can't be pickled—open file handles, database connections, or certain C extensions. If you hit serialization errors, test your function locally first or consider using ray.put() for large objects.

When you call process_data.remote(10), Ray packages the arguments, sends the work to a Raylet, and returns immediately—without waiting for the result.

ObjectRef: The Receipt for Your Work

What you get back isn't the result—it's a reference:

result_ref = process_data.remote(10)

# result_ref is an ObjectRef, not the number 20Think of an ObjectRef as a receipt. It says "your result will be in the object store at this location." The actual computation might still be running.

When you call ray.get(result_ref), you're saying "I need the actual result now." If it's ready, you get it immediately. If not, ray.get() blocks until the task completes.

Why This Matters: Avoiding Re-Serialization

Understanding ObjectRefs prevents a common performance mistake:

# ❌ Bad: Serializes huge_data 100 times

huge_data = load_big_dataset()

results = [process.remote(huge_data) for _ in range(100)]

# ✅ Good: Store once, pass reference

huge_data_ref = ray.put(huge_data)

results = [process.remote(huge_data_ref) for _ in range(100)]In the first version, huge_data gets serialized 100 times—once per task. In the second, it's stored once in the object store, and tasks receive a lightweight reference.

This is why Ray's object store exists: efficient data sharing. Tasks and actors pass around references, not copies of the actual data.

Back to our office analogy: when employees need data, the regional manager doesn't photocopy the entire file for each person. Instead, they say "the data you need is in file room cabinet B, slot 47." Multiple employees can reference the same data without making copies.

You don't usually think about this—Ray handles it automatically. But knowing ObjectRefs exist helps you avoid accidentally serializing large data repeatedly, which kills performance.

You Now Understand Tasks and Actors

When you started this post, @ray.remote was just a decorator that "made things distributed."

Now you know the distinction:

- Tasks are stateless workers—perfect for parallel, independent operations

- Actors are stateful coordinators—ideal for expensive initialization or persistent state

- The power pattern combines them: actors orchestrate, tasks execute

You understand ObjectRefs aren't the data itself—they're references to the object store. You know that actors process one method at a time, but can dispatch hundreds of parallel tasks. You've seen the decision tree: does it need memory? Use an actor. Is it embarrassingly parallel? Use tasks.

At Mechademy, this mental model changed how we architected ML pipelines. Training coordinators became actors. Feature engineering became tasks. Artifact generation became actors that dispatch plotting tasks. The system stopped fighting us.

What We Didn't Cover

We haven't talked about what happens when things fail. What if a worker dies mid-task? What if an actor crashes? How does Ray handle fault tolerance and recovery? We'll explore that in a later post.

We also haven't explored how Ray decides where to run your code. Why did this task land on node 3 instead of node 1? How do you control resource allocation? How does Ray optimize for data locality?

That's Part 4: Scheduling and Resource Management.

Try It Yourself

import ray

ray.init()

# Experiment: Create an actor that dispatches tasks

@ray.remote

def compute(x):

return x ** 2

@ray.remote

class Coordinator:

def __init__(self):

self.results = []

def process_batch(self, numbers):

refs = [compute.remote(n) for n in numbers]

batch_results = ray.get(refs)

self.results.extend(batch_results)

return len(self.results)

coord = Coordinator.remote()

ray.get(coord.process_batch.remote([1, 2, 3, 4, 5]))Watch how the actor stays alive, accumulates state, and dispatches parallel tasks.

Next time: We'll dive into scheduling—how Ray decides where your tasks and actors actually run, and how you can influence those decisions.

See you in Part 4.